Following the Christmas Day capture of a passenger, dubbed “The Underwear Bomber,” who attempted to blow up an American airliner, controversy swirls around the use and efficacy of full body scanners and the fate of the images they generate. At present, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) is considering two types of scanning technologies to upgrade its passenger screening systems.

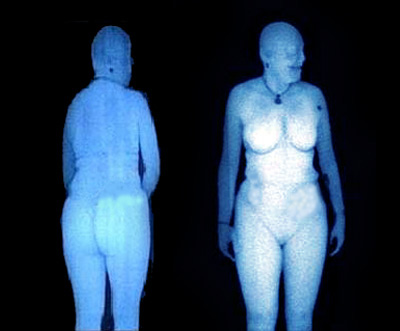

The first kind, millimeter-wave sensors, emit radio frequencies to produce pairs of detailed, front-and-back, 3-D images of passengers that look like photographic negatives, and can detect detect liquids and other potential explosives hidden beneath clothing. Click here to see some sample images.

A second technology being promoted involves backscatter x-ray scanners, which send out low-intensity beams to create a single-sided image that reveal objects carried on passengers’ bodies. To see samples of those, click here.

Full body scanners—dubbed “naked scanners” by those who characterize the security measures as “virtual strip searches”—are, it turns out, already in limited use. According to the New York Times,

full-body imaging machines are in place in nineteen U.S. airports and are the primary method of screening at six. A recent article in BusinessWeek reports that 300 advanced scanning imagers are on order and ready for delivery in 2010, and that prices for shares of stock in companies producing the technology—including Rapiscan, Smiths Group Plc., and L-3 Communications Holdings Inc.—are on the rise.

Whether scanning will or will not contribute to airport congestion and security lines is debatable. Scans take from 20-45 seconds per passenger, although they cut down on the time spent removing shoes, coats, belts, and other concealing articles of clothing. But central to discussions about the use of scanners are privacy and legal issues, such as what, exactly, the images will show. According to manufacturers and the TSA, details of facial features and of other body parts will be blurred when screeners take, see, and scrutinize the images. Screeners will be located in a separate area, away from the scanners, so they will never see the passengers being screened. Security personnel stationed at the scanners will never see the scans that are made. The TSA says it will not keep, store, or transmit images. To get a sense of what the process is like, here’s an ABC News video showing a reporter testing out the process.

So, with all these assurances, why are some people still voicing concern? Surveys show that while many are willing to be scanned head-to-toe for security’s sake, others are nervous. Given recent examples of supposedly-secure digital information that’s been leaked or become available, some skepticism is understandable. Would images that, for example, reveal breast implants or prosthetic devices a breach of privacy? Are scans made of children the equivalent of child pornography in certain locales and states? While it’s not a national security issue, will images of well-known people wind up on Internet gossip sites? Is scanning be offensive to those whose religions forbid them from being seen naked?

The scanning debate raises an interesting question; is visibility a guarantee of public safety? Some security and terrorism experts suggest that other measures, such as tightening up visa reviews in high risk countries, might prove to be just as effective. So, let’s wait, watch what happens, and revisit the story when more news breaks.

Produced by the Smithsonian Institution Archives. For copyright questions, please see the Terms of Use.

Leave a Comment